Forging a partnership of the Digital and Vernacular–James Stevens, Director at makeLab™

By Purva Chawla

The terms 'Digital fabrication' and 'Digital Architecture' bring to mind images of sleek, futuristic and utopian feats of design and construction. On the other hand, the term 'Vernacular,' in the context of architecture, conjures almost diametrically opposite imagery–earthy, gritty, low-tech and rooted in local tradition.

These two divergent streams of thought and practice can certainly intersect, though–a realization that comes from seeing the work of Prof. James Stevens, Director for makeLab™–the digital fabrication lab at Lawrence Technological University's College of Architecture and Design.

James, who is Chair and Associate Professor of Architecture at Lawrence Tech., is responsible for reconciling digital and vernacular approaches to architecture and creating a new space for architects and makers to operate in. This space lies at the junction of grassroots projects and resources, with the digital tools and fabrication techniques that makers have access to today.

MakeLab™'s handmade mud-brick emerges from a digitally-controlled milling block (Top image), to create the final result, seen above.

This unique way of generating architecture, spearheaded at makeLab™, presents an opportunity to make an impact at multiple scales of building, and in diverse contexts. This approach paves the way for architects and makers in different parts of the world to employ tools easily available to them, towards making contextual architectural solutions, and also to build some of this digital fabrication toolkit themselves.

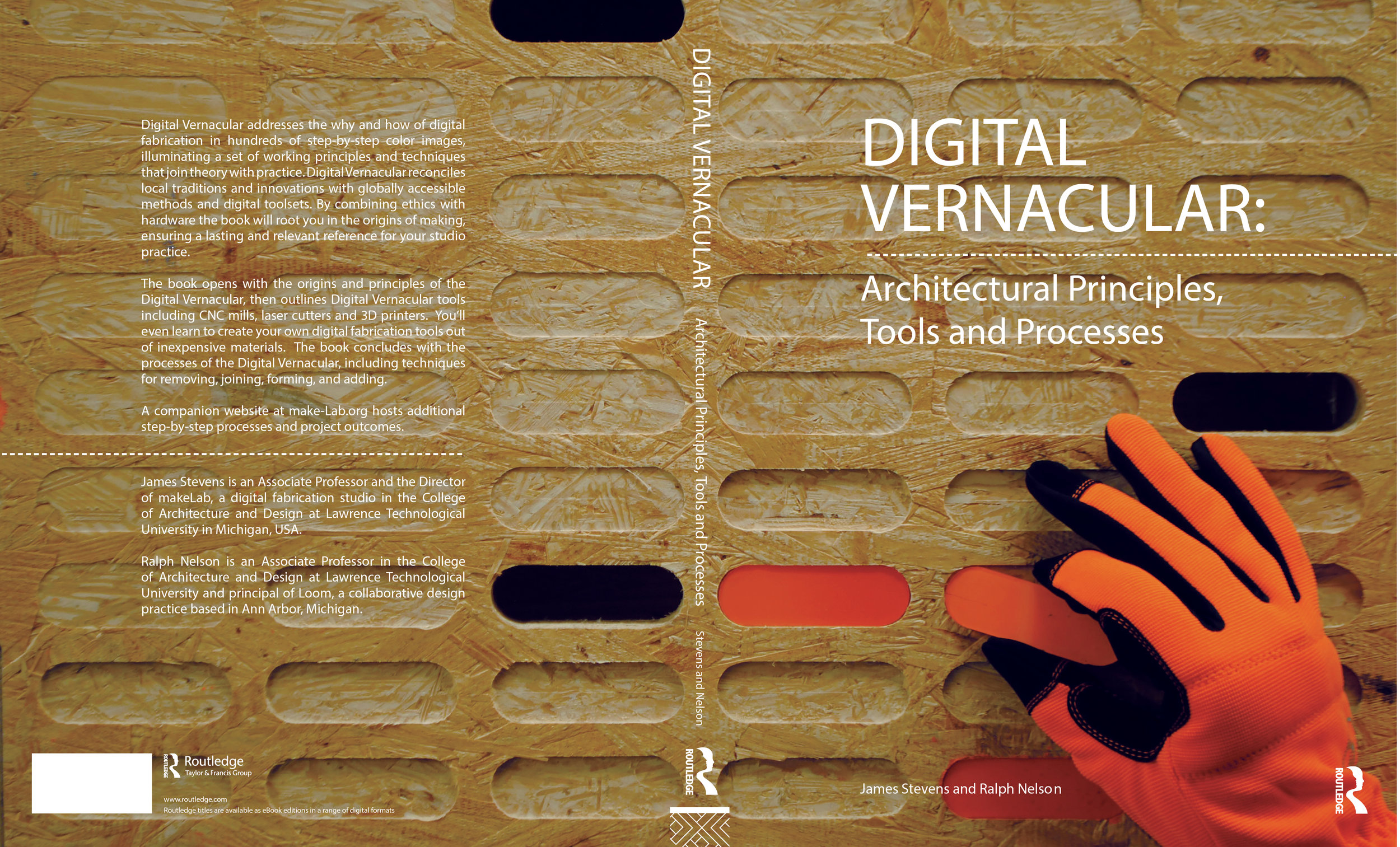

This partnership of digital and vernacular, emergent at makeLab™, became the foundation of 'Digital Vernacular'–a book co-written by makeLab™ Director James Stevens and his colleague, Associate Professor of Architecture Ralph Nelson. Also instrumental was Ralph Nelson's experience as founding principal of Loom, a collaborative practice of art, design, and architecture that has been recognized for orchestrating minimum resources to maximum effect.

'Digital Vernacular,' released in 2015, addresses the whys and hows of digital fabrication, illuminating a set of working principles and techniques that connect theory with practice. With this book, the two authors wanted to reconcile local traditions and innovations with globally accessible methods and digital toolsets.

Readers of 'Digital Vernacular' can understand the origins of the digital fabrication tools they are familiar with today, pinpoint the origins and influences of their own making process and build the tools they will need to execute digital fabrication with basic resources.

The emergence of makeLab™

In 2009, at the peak of the Recession, James Stevens, a professor of Architecture at Lawrence Technological University in Michigan found himself surrounded by talented architects who knew how to create things but had no jobs. At the time, they couldn't access the corporate infrastructure responsible for building architecture.

This pushed Stevens to found MakeLab™, in 2010, to foster an entrepreneurial attitude to making–encouraging such architects and makers to build their own projects, in grassroots contexts. The goal was to employ the most common digital tools and materials, using what James Stevens calls 'Medium-tech.'

Contrary to the perception of a revolution, the intent here was simply to place digital technology in the right place in architecture.

While design today often romanticizes digital tools and their utopian output, the purpose at makeLab™ has been to ground these tools and principles in the present.

makeLab™ workshops

In that spirit, James Stevens and several of his students involved with the makeLab™ have conducted workshops in and traveled to locations as diverse as Albania, Bolivia, India, Paris, Romania, and Kosovo.

Through these workshops and experiments, there have been efforts to coalesce local traditions of building, with digital technology and to set up digital fabrication labs in diverse contexts.

In some cases, that has meant developing digital fabrication tools for an emerging economy (Albania). While in others, it has meant crafting with indigenous materials and local masons–exploring a three-way relationship between 'Man, Machine, and Material.' This latter scenario responds to a question that is often asked at makeLab™: "If the technology we create and employ can't work with indigenous materials, is it even viable?".

A makeLab™ workshop in Northern India explores 'Digital ornament'. Seen here is the finishing by hand, following digitally-controlled processes.

Exploring this realm was key to a recent workshop, titled "CYBORG CRAFT: MASONRY WORKSHOP," that was held at India's CEPT University, in June this year. The workshop was led by Prof. Stevens and Ayodh Kamath, Assistant Professor of Digital Design and Fabrication Technologies at Lawrence Technological University.

This design-build workshop involved feedback between designers, skilled human masons, a CNC machine, and a computer algorithm. First, students learned to design three-dimensional surfaces using Rhinoceros 3D surface modeling software. These virtual surfaces then became the input for a computer algorithm to facilitate information exchange between local, skilled masons and a CNC machine.

The feedback enabled a brick wall to be created, pairing geometric complexity from the computer with creative improvisation by the masons. While the result was an imperfect wall, both the students and local masons were quick to understand that the 'back-and-forth' between the computer, digital CNC and the masons was the real design project, not the form of the wall itself.

makeLab™ projects

This workshop, and like it, many others, was enabled by a monumental invention called the 'Suitcase CNC.' In 2012 James Stevens and makeLab™ launched the 'Suitcase CNC' – a three-axis CNC machine that could be checked onto an airplane and carried anywhere in the world.

This demanded that the machine weigh less than 50lbs, stand up to abuse, and be quickly set up and broken down. This incredible machine not only paved the way for numerous collaborations and experiments outside of the US for makeLab™ but is the precedent for many digital-vernacular tools that can be made by architects on their own, in any part of the world.

The creation of the 'Suitcase CNC' at makeLab™ , paved the way for international workshops and experiments such as this where digital cutting and milling in being performed in North India.

Despite such innovations, the goal at makeLab™ is not for architects and makers to become high-tech machine builders or industrial designers. The idea is to use existing machinery (some even prevalent from the 1950's). There is also a strong emphasis on working with the most typical, or traditional materials.

A project by makeLab™ student Brent DeKryger comes to mind here: DeKyrger's project focussed on the slip casting of ceramics. The slip cast project explored how traditional techniques of construction could be altered by digital fabrication to reveal new design potential. The conventional process requires plaster mold that receives the liquid clay slip. The slip is poured in and out of the mold to form the hollow ceramic unit. By casting a plaster "blank" and using a subtractive process on the CNC machine instead, it is possible to customize the mass production of ceramic slip-cast units, which can then interlock and serve as cladding masonry.

This project also illustrates a key theme in most of makeLab™'s projects– work that is grounded in the present but also rooted in the past. Every project at makeLab™, James says, "Begins with the guiding principle of the knowledge of the past. Then we determine how we want to proposition the future."

makeLab™''s students create a mockup of a wall, using digitally-milled bricks.

Occasionally there have been questions about the scale of these projects, with references to "furniture," more than architecture. An excellent response to this was makeLab™'s proposal for the Pristina Mosque. The Central Mosque of Pristina design was an international collaboration between makeLab and many firms in Italy, Albania, and Kosovo.

MakeLab's efforts were focused on the development of a building skin inspired by traditional Islamic screens. Through an extensive and iterative process, makeLab™ displayed how the digital vernacular approach could be implemented at a massive scale in an architectural project and was in no way only applicable to smaller, grassroots works.

James Stevens' work at makeLab™ seems to say very firmly: "We can't ignore the time or place we are living in." The work at the lab and the teachings of 'Digital Vernacular,' instead prepare a breed of skilled professionals with a digital-vernacular sensibility who can carve out new ways of being responsible architects.