Advanced Geometries, Advanced Materials–In conversation with Orproject

Overlapping wafers of Polypropylene fused with photochromic dye. Polygons of paper stitched together, each with its own folded supporting 'paper beams.' Plastic, molded and vacuum-formed into lightweight, doubly-curved panels.

These are just a few elements of the extensive vocabulary of material components and fabrication techniques from international architecture and design practice Orproject.

Orproject is an architecture and design practice established in 2006 by Rajat Sodhi, Francesco Brenta, Christoph Klemmt and Haseb Zada with offices in New Delhi, London, Beijing, and Dubai. Their work explores advanced geometries with an ecologic agenda, the integration of natural elements into design resulting in an eco-narrative unfolding into three-dimensional spaces. Orproject's work has been published and exhibited widely, amongst others at the Venice Biennale 2016, London Architecture Festival, the Furniture Fair in Milan and at Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

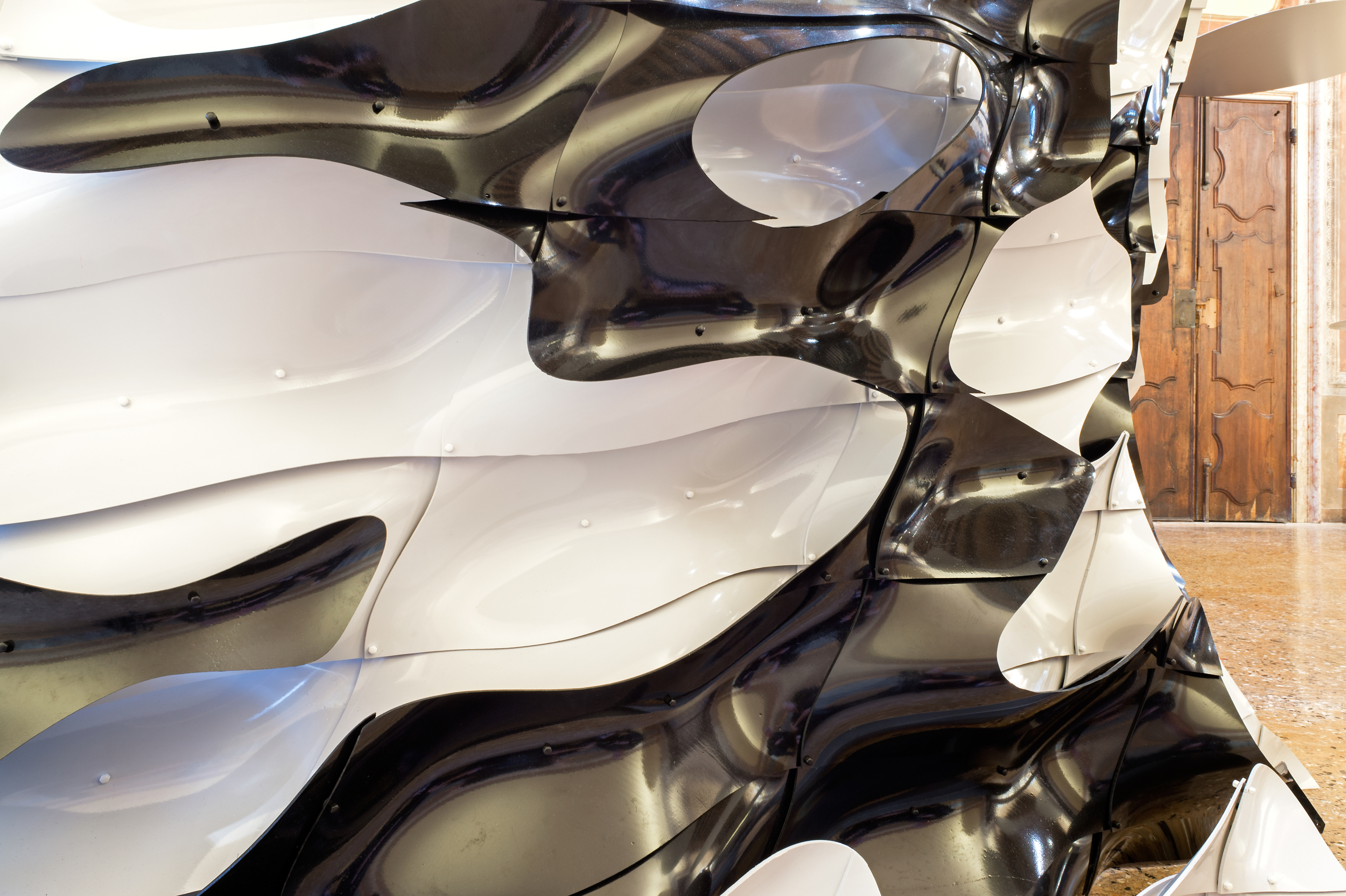

First up in our conversation was Sahya, Orproject's newest installation, and exhibit, currently on show at the Palazzo Mora in Venice, as part of the prestigious Architecture Biennale di Venezia 2016 or Venice Biennale for Architecture 2016. The wave-like form, roughly 1.5 meters high and 3 meters long, is a self-supporting three-dimensional lattice of doubly-curved panels, made of ABS plastic. The lattice of panels acts as both a wall and roof system and controls light entering into the interior, while also directing the flow of wind into the structure.

Sahya is intended for large scale use–as a shading pavilion and a facade system–and stands out for its sustainable, lightweight, easily transportable and constructible qualities. For its current installation, its 200 curved panels were simply stacked and shipped to their current location.

Understanding the individual component–the doubly-curved plastic panel-became infinitely easy when Rajat showed me the sculpted, solid aluminum mold that the panels had been pressed onto, the curved wooden molds they were trimmed on, and the vacuum-forming process, via video. None of these tools or ingredients of the fabrication process appeared to be standard or often used by other designers. "We almost always work with new materials, materials which may not be available off the shelf," Rajat stated.

Viewing the doubly-curved panels of Sahya, by Orproject at the Palazzo Mora

It was interesting to learn that much of Orproject's work was the result of coaxing and an extensive back and forth with material suppliers and fabricators. It became apparent that with each engagement, Orproject used a single, newly crafted or modified material as well as fresh and cutting-edge techniques of production and assembly.

Clearly, Orproject follows a method where its design team lays out the entire fabrication process for each component, before reaching out to fabricators and suppliers. This is useful in bringing them on board for what is, undoubtedly at first, an experiment.

Another interesting learning was the design intent behind each project that we discussed. Much of what one sees as the built outcome originates in Orproject's research into material systems, venation systems, and geometries that provide structural stability. Concepts such as cell division and cell growth, the physical manifestation of music in architecture, among others, then help dictate the form of the often tensile systems.

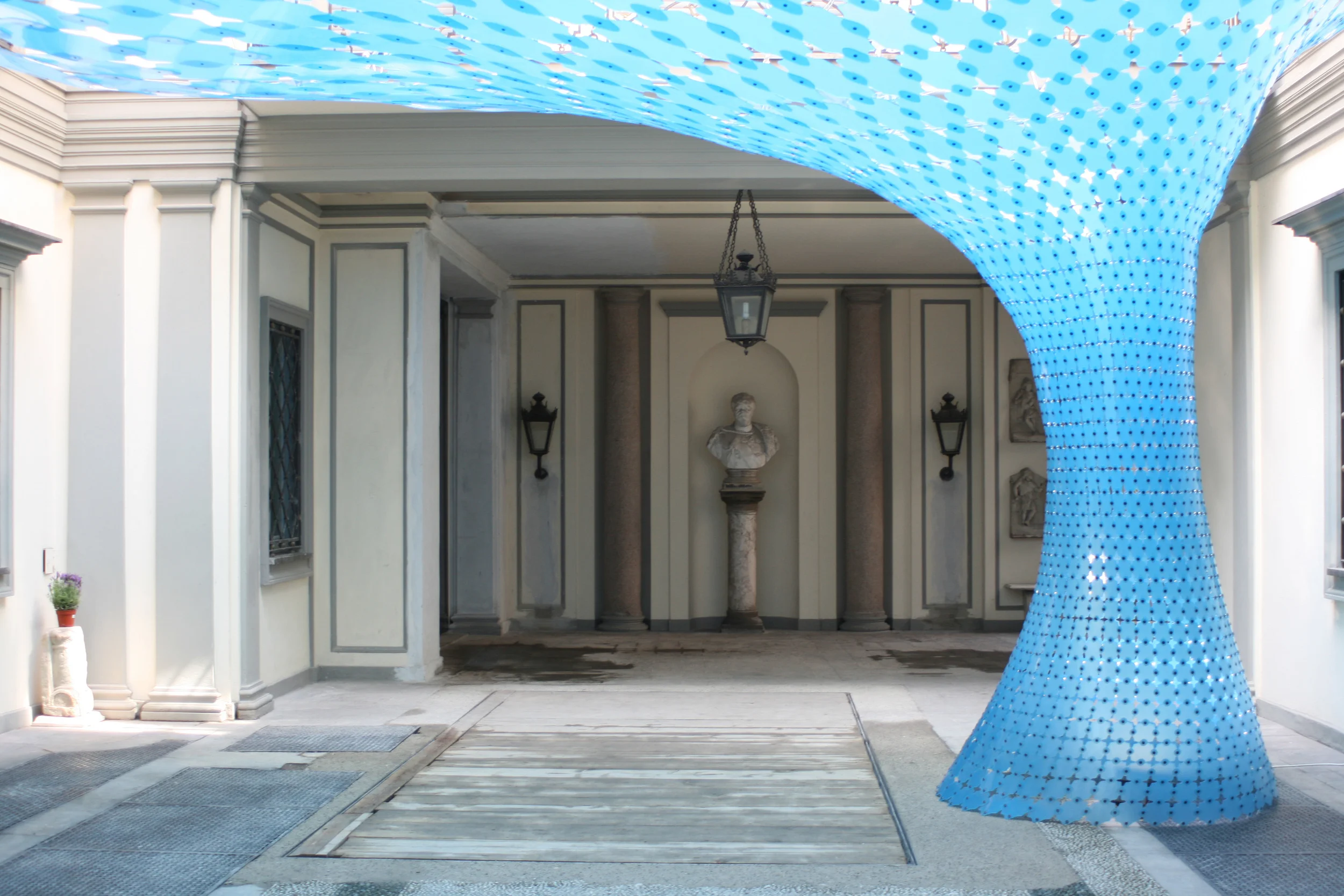

Speaking with Rajat, I also became better acquainted with the installation duo of Or1 and Or2, which were among my favorites from the Orproject camp. While the technique used to weave the individual propylene components was different in the two, the tree-like tension structures had one exquisite quality in common–their response to light. Both were steps in exploring the possibilities of photoreactive materials in the fields of furniture and design.

Or1 by Orproject responds to sunlight, at the Milan International Furniture Fair 2008,

Or1 is translucent white, in the shade, at the Milan International Furniture Fair 2008,

The small photochromic individual panels were the result of an amalgamation–conventional propylene with photo-sensitive dye-used, until then, only in the medical industry. The result was that the two installations responded to natural light during the day with different hues, before returning to a pristine white at night. Additionally, in the case of OR2, the pieces themselves were cold-bent to a slight curve, to accentuate the effect of light.

Or2 respinds to sunlight, at Italian Cultural Institute in Belgrave Square, London

I was thinking about this elevation of materials, using diverse ingredients and techniques, when Rajat said: "We aren't just interested in what a material is, but what it can be when we bend it, curve it, mold it, or weave it– enhancing its structural capacity.” That statement was validated even further when we talked about projects like Vana and Dynamorph (exhibited during the previous Venice Biennale for Architecture, 2014). Here, humble material like paper rose to the status of a structural component. From creating small folded beams to support the paper polygons, to understanding how light reacted with the thickness and starchiness of paper to spill different hues of light into space, the design team from Orproject delved into it all.

Dynamorph at the Venice Biennale for Architecture, 2014

Vana by Orproject, as seen when it responds to light.

Vana by Orproject, as seen when it responds to light.

Vana by Orproject, as seen in the absence of light.

Another quality of Orproject's work that struck a chord with me was the efficiency and sustainability of materials–all resultant from the methods of fabrication.

In the case of Anisotropia, which is a physical manifestation of music, the wooden facade was made of strips of a bamboo lamella. The thin layers, stacked together and woven this way, were extremely strong and structurally stable. The alternate to achieve this stability would have been carving from a large chunk of wood- an immense wastage of material and a costly solution.

In the case of Sahya and other work using ABS plastic, all process molds, and even leftover panels can simply be crushed to their base, granulated form, and recycled one hundred percent.

Anisotropia at the China National Museum, Tian An Men, Beijing, is the physical manifestation of a frozen piece of music.

On a final note, it was incredibly fascinating to learn about how Orproject was pushing a single material to its limits in each installation–the one material, which acted as both skin and structure were rarely supported by any secondary material or framework.

At the end of my visit to the Orproject office, and conversation with Rajat, I left with a wealth of information, an in-depth understanding of Orproject's work and an expanded definition of the role that designers can play in determining materials and fabrication.

Strips of Bamboo lamella at Anisotropia at the China National Museum, Tian An Men, Beijing.