'Ten-thousand hours and Transferrable skill'–Patricia Mato-Mora captures what it means to be a 'Master of Material'

By Patricia Mato-Mora

Over the course of the past two and a half weeks, MaterialDriven has presented the work of five artists and designers whose work is inseparable from the material it is made of, and whose craftsmanship has been deemed remarkable by our editorial team.

Each of these practitioners works within the idiosyncrasies of their material of choice, whether it is acrylic paint, clay, paper, ice or resin. Their mastery is manifested in the ability from the part of the maker to induce a physical behavior or configuration not easily exhibited by the material otherwise; or by their ability to convey meaning and purpose beyond the raw state of said material. These two loose categories aren’t mutually exclusive - one perhaps presupposes the other.

You would be forgiven for thinking that Brian Huber’s creations can’t possibly be made out of sheets of acrylic paint, carefully sliced and arranged into beguiling organic patterns. During his lecture, Matthew Shlian’s work amazes his audience. “What material do you use to make these works?”, They ask, not fully believing that they are made of humble paper. Saerom Yoon controls the coloring of resin to create his much-loved 'Crystal Series' furniture, and Joshua Abarbanel works with water across its solid and liquid states with an ease that enables him to raise questions about presence and impermanence. My work attempts at blurring the boundary between what we imagine to have been made by a non-human animal, or one of our bipedal counterparts.

Each of them has found their voice in a certain material, though this wasn’t their first or obvious choice. Instead, they have arrived at their current way of working by following a thorough interrogation of their processes and methods.

While it is true that their current work is manufactured by sticking to a single material, and relentlessly exploiting its possibilities, there is something else that all five interviewees have in common, besides their expertise. Namely, a transference of skill from one material to another, which didn’t happen straight away in their professional life. In other words, their affair with materiality started elsewhere. It seems to me that each of them has found their voice in a certain material, though this wasn’t their first or obvious choice. Instead, they have arrived at their current way of working by following a thorough interrogation of their processes and methods.

Shlian’s pursuit of the potential of paper started while enrolled in a ceramics program. Conversely, my own journey started among architectural drawings and models (and the spaces they imagined), and landed me in the world of ceramics that Shlian left behind. Huber also departed from an interest in space and spatial choreographies and developed his mastery of paint at a later date. Yoon and Abarbanel first set off to materialize their ideas in timber; and there must be something they both encountered in the process that led them to explore the crystal-like qualities of resin and ice, respectively.

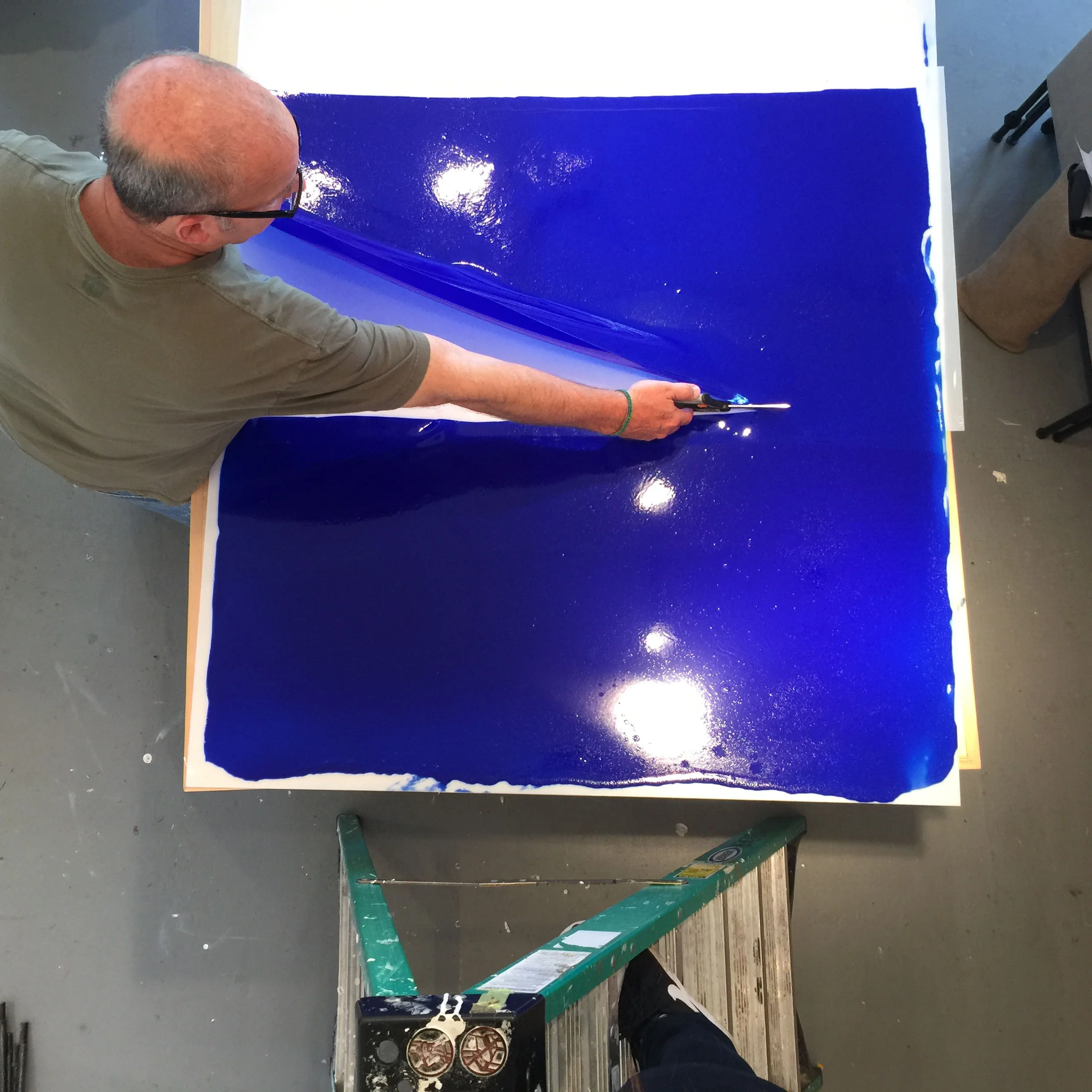

Brian Huber, developing his mastery of medium–molding sheets of dried acrylic paint.

My first pottery instructor used to encourage us novices by explaining that “his first ten thousand pots” had been the worst he’d even thrown on the wheel. Ten thousand, no less. Although mastery is said to derive from devoting oneself to a single activity for at least ten-thousand hours, or ten thousand pots, in the case of the pottery wheel (which, I think, amounts to more than ten thousand hours); A phenomenon is easily observable in the work of all five “Masters of Material”, which is that of transferrable skill. That is, they might not have needed a whole ten thousand hours to understand the way their second material of choice wanted to behave.

Indeed it is, I believe, a virtue of getting to know the particularities of a certain material with a previous awareness of another, that they have been able to push their current work beyond what the material dictates; introducing unique artistic expressions and sensory qualities. It was through taking steps in a different direction that they were able to identify what they wanted to say as artists or designers, and had to turn down or pause their first choice in order to convey a certain message. To conclude, may I venture to say that thanks to this journey their thinking has now become inextricably linked to the material they work with.

About the author

Patricia Mato-Mora studied architecture at the Architectural Association; and obtained her Masters at the Royal College of Art, where her dissertation A Single Ecstasy was awarded a Distinction.

Patricia currently teaches architecture and interior architecture at the Architectural Association, and the University for the Creative Arts respectively. Her work has been published in AArchitecture, The Architectural Review, and The Journal of Modern Craft.

This article is her first contribution to MaterialDriven, and one of many to come.

Learn more about Patricia's work and writings here